By Abdul Rashid Agwan

Peace is an essential requirement of any human development including the quality education. The nations and societies that face recurring violence, conflict and communal tensions are badly affected in terms of educational attainments. On the other hand, education itself is required for sustaining peace and harmony in society. India’s backwardness in quality education inter alia other reasons may also be due to dearth of social harmony in the country. Not only the native society but also educational institutions here have become battle grounds of caste and communal strife, resulting into general and sectional backwardness in education. The tendency to contain fruits of development for certain elite sections of the country or even to monopolizing them for a few castes, is badly affecting educational and scientific advancement in India.

UNESCO’s outcome report of an international expert seminar on ‘Protecting Education from Attack’ held in Paris in 2009, states, “Education is a fundamental right – both an end in itself and an enabling right; access to good quality education enables people to secure and enjoy other rights.”[1] However, wars and conflicts deny them this right to a great extent by what the UNESCO sees as “attack on education.”Evidently, violent situations in any society not only jeopardize educational development of vulnerable sections but their education itself becomes a target of attack by aggressive groups including the state machinery dominated by them. Though India has been witnessing communal situations including occasional genocides, even before it got freedom, some recent developments have aggravated the situation, making it critical since 2014. There is no doubt that Muslims are the worst sufferers of the prevailing scenario. Therefore, it is required to understand the overall situation and come out with an action plan to ameliorate it.

The Situation

The controversial elopement of Najeeb from India’s premier institution Jawaharlal Nehru University in October 2016 after communal turmoil in the campus, communal attack on Aligharh Muslim University in the name of Jinna portrait in May 2018, banning Hijab for CBSE’s AIPMT entrance examination in 2015, attacks and agitations against Kashmiri students in different parts of India, false cases of terrorism against meritorious students studying in eminent institutions of the country, making government policies that directly affect educational prospects of the already marginalized sections and torture and bullying of students in campuses and hostels and the like are some of the recent episodes which speak volumes as regards threats to Muslim education in India. The emerging situation is not only threatening educational development of Muslims but also that of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, other minorities and other vulnerable sections of the country.

The recent most incidence of Payal Tadvi’s suicide rings the alarm bell and reminds of the suicide of Rohith Vemula in January 2016. Muslims’ silence on the forced suicide of Payal Tadvi, a 26 year-old second-year MD student at Mumbai’s TN Topivala National Medical College (TNMC), on 22 May, shows their sheer ignorance that she belonged to a Muslim tribal community called Tadvi Bhil. She committed the undesirable act due to continuous intimidation and casteist aspersions by some upper caste classmates. She was harassed and mentally tortured by her seniors on racial ground and was found dead in her hostel room. Her death is a tragic reminiscence of the suicide of Rohith Vemula, who was also 26 when he hanged himself in his hostel at University of Hyderabad alleging caste discrimination at the hands of the college administration. The whole nation became agitated on the latter’s case but there is utter silence on that of Payal’s. The suicides of Payal and Rohit are not some isolated cases, there are thousands of reported and unreported cases that make campuses today the new slaughter houses of the country.

Union Minister of State for Home Hansraj Gangaram Ahir informed Rajyasabha in March 2018 that nearly 26,500 students had committed suicide in India from 2014 to 2016, almost 24 per day.[2] While 8,068 students had committed suicide in 2014, the number increased to 8,934 in 2015 and to 9,474 in 2016, a steady rise of the carnage. Maharashtra, where Payal Tadvi sacrificed her life on the anvil of social hate, topped the states in terms of such suicides all these years. It has also been reported that around 75,000 students committed suicides in India between 2007 and 2016, about 30% of these suicides were due to academic failure and rest due to other reasons.[3] From 6,248 the incidence has grown by 51% in a decade’s time. Divya Trivedi admits in her article in Frontline, “Socially discriminatory practices against students from marginalized communities in educational institutions are among the major factors that have led to a rise in the number of suicides on campuses.”[4] The suicide note of a Dalit student of JNU who was found hanging from a ceiling fan on 17 March 2017 in Delhi is an eye opener, who painfully remarked, “There is no equality in MPhil/Phd admission, there is no equality in viva-voce, there is only denial of equality, denying Prof. Sukhadeo Thorat recommendation, denying students protest places in the Ad block, denying the education of the Marginals. When equality is denied everything is denied.”[5] This appalling situation in India is likely to hamper the educational development of a large population if remain unabated.

Suicides among students are typically attributed to “depression, academic pressure, family expectations, inability to cope with stress, social isolation and substance abuse.” More than often, the social and structural problems leading students to feel hopeless remained unrealized such as economic problems and caste-based and communal discrimination. The cases of bullying and soft torture of students on the ground of their religion, caste and ethnicity must be manifolds then the reported cases of suicides. A noted journalist and Magsaysay awardee P. Sainath has criticized those who try to justify these plethora of suicides of students on the ground of academic depression saying, “…there is a more cruel and venomous insinuation in this.”[6] The Thorat Committee found that 72 per cent of students (primarily Dalits) were discriminated against, and more than 90 per cent of them complained about being humiliated during practical and oral examinations.[7] This is a gory reality of the so-called ‘New India’. Institutions like the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) are infamous for suicides by students. The other professional institutions are not behind in this regard.

Impact of Communalism on Educational Development

Though there is a dearth of studies in India regarding the impact of communalism on educational progress of Muslims and other minorities, however, some stray studies referred here may give an idea how the communal tensions affect the vulnerable communities.

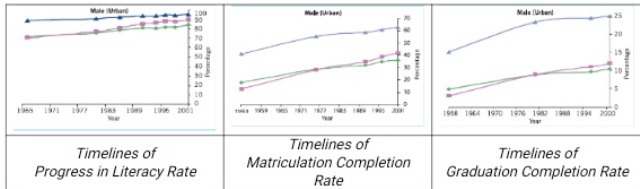

Sachar Committee Report has described timeline of progress of different social groups on various fronts of education, while comparing data of Muslims, SCs/STs and All Others.[8] The Charts contained in the report reveal that during communally the highly charged decades of 1980s and 1990s, the educational graph as regards Urban Muslim Females, Rural Muslims Males and Females were slightly lowered but those of the urban Muslim males there has been a sharp decline in the progress of their literacy rate, matriculation completion rate and graduation completion rate. Obviously, the sensitive urban Muslim males who have been facing communal prejudice at various levels through all these years have been greatly affected by the adversity of the situation. The charts illustrate that up to 1983 there was a general upward trends of Muslim literacy, matriculation and graduation completion rates, which were without acceleration thereafter up to 2001. This is a clear evidence how communal situation affects educational attainments of the community which faced the issue of Shah Bano and Babri Masjid and Draconian laws of TADA and POTA all these years.

Sometimes the areas affected by communal riots may lead to some positive changes as well, as could be seen from the example of Gujarat. Raheel Dhattiwala writes in his analytical report of 2006, Muslims of Ahmedabad: Social Changes Post-1993 andPost-2002 Riots, thus, “It happened that in Ahmadabad city, of the 59 Muslim-run government recognized private educational institutions, 68% were established between 1992 and 2005 (that is, between the communal riots post Babri Masjid demolition and those post Godhra). The rest 32% can be said to have come up in a span of over 100 years.”[9] Among the 15 private Muslim-run schools in Ahmadabad that got established between 2002 and 2005, 8 began in 2003 – the year after the carnage, Dhattiwala reports. Similarly, the percentage of Muslim as compared to total doctors in the state has gone up to 15% after 2002 though Muslim population in Gujarat is 9%.

However, these are some bright developments. The overall educational situation of Muslims in Gujarat had shown unpleasant signs since the Godhara genocide. According to 2001 census, Muslim literacy in Gujarat was recorded as 73.5% as compared the state’s 69.1%. However, the NSSO 66th Round mentions that Muslim literacy had marginally increased to 74.3% in 2004-05 whereas the state literacy rate has also become at par with it being 74%.[10] This underlines a general deceleration of Muslim literacy rate in the state presumably in the wake of communal situation that erupted after the Godhara riots. Yet, there are signs that Guajarati Muslims have overcome the adverse situation. The state education minister quoted data that shows Muslim literacy rate in Gujarat has become 80.80 per cent in 2011, as against 78.03 in the state. Socio-political activist Zuber Goplani, who is also a member of multiple Muslim educational trusts and runs the Hanifa School in Borsad, Anand, says, “The incident of 2002 played a major role in awakening the Muslim community about the importance of education in life. Until that time, the community was seen as being least interested in education and therefore also looked down upon as having no contribution to make to the development of the country. The community has realised that to be heard, to be represented and to be able to stand up for their rights, they need to be educated. In Gujarat, the number of schools run by the Muslim community has gone up from 198 in 2001 to 1,000 in 2018.”[11]

A perfect example of communal impact may been in the North-South divide of the Muslim community. In 10 southern states, Muslim literacy rates have been noted as better than the general population in the last two censuses, whereas Muslims in such large states as Rajasthan, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal and Assam are lagging behind other communities on this parameter. The southern Muslims are also leading their counterparts in the north in terms institution building with large number of schools, colleges and professional institutions. One basic reason for this glaring divide is comparatively higher incidence of communalism in the northern states, where Muslims are pushed to think of only survival and identity and nothing else.

Using Education for Peace or Prejudice

Grahm K. Brown analyzes the interrelatedness of peace and education in these words, “Education is rarely directly implicated in the incidence of violent conflict but identifies three main mechanisms through which education can indirectly accentuate or mitigate the risk of conflict: through the creation and maintenance of socio-economic divisions, including horizontal inequalities between ethnic groups; through processes of political inclusion and exclusion; and through accommodation of cultural diversity. It further suggests that designing conflict-sensitive education systems is particularly problematic because the implications of these three principal mechanisms often pull in different directions.”[12] Thus, it is evident that not only education is harmed by disharmony in a society it is also sometimes used as a tool that spawns discord and division among people. The writing and rewriting of history books become vital in this regard which can be used for either uniting or dividing society. The present environment is for the latter. The textbooks are being prepared in such a way that some of the communities are shown as villains of history which creates a prejudice and bias at every level of execution of schemes of education and thus horizontally divides the society in a subtle way.

Direct Impact of Conflicts on Education

Any violent situation is bound to cause severe damage to educational prospects of common people in general and the vulnerable sections in particular. Here are some major consequences of conflict and tension in a society.

- National Loss: There is no doubt that disruption of peace and harmony in any country has been regarded as a great national loss. According to the Institute for Economics and Peace, India lost nearly 9% of the GDP in 2017, with every Indian loosing Rs 40,000 each. This is a big loss in itself. Just compare this loss with the government allocations in education which generally remains at 3-4% of the GDP. If this loss is prevented and used for the educational advancement of the country, it could soon become a developed country, a dream so far belied.

- Decline in the Quality of Education: A Kenyan study have shown that “inter-clan conflicts have resulted into inadequate syllabus coverage, teachers did not felt accountable to the learners and inefficient professional practice among the teachers during tribal conflicts.”[13] Another study establishes that “conflicts do affect residents’ educational interaction, children/ wards’ functionality of and accessibility to schools during and after conflicts in southwestern Nigeria.”[14] Perhaps the same applies to India too where social conflicts lead to temporary closure of schools in the affected area which seriously affect their educational performance. In states and places where the frequency of conflicts is high, either the local children are glaringly deprived of education for a longer time or many of their parents choose to shift to some normal areas where their children could pursue education. This may cause financial burden on them. Moreover, such frequent changes of institutions and geography often spawn psychological problems among the growing up children.

- Damage to Infrastructure: In certain cases, communal riots lead to damage of the institutional properties both under the government or privately ones. It takes years together in rebuilding the destroyed infrastructure and hence this imposed deficiency may affect quality of education imparted by such institutions. Establishment of institutions requires heavy investment and many a time this loss cannot be overcome for a long time.

- Economic Deprivation: Economic loss during riots becomes a major hurdle in getting education in near future as rehabilitation becomes the major concern of the affected families.

- Displacement: During and after riots, displacement of large number of families from their traditional dwellings is a fact. This causes deep dent in the educational prospects of the vulnerable communities. Komol Singh reported from her study of Manipur that the conflict does not affect educational growth, but it pushes the children out of the state for their studies.[15] However, this kind of opportunities could be availed only by limited number of students. The story of Kashmiri students is more pathetic. They cannot avail good education in their state due to disruption and in other states communal organizations make their educational engagements difficulty due to protest and hatred against them.

New Education Policy on Peace and Harmony

Now, the Draft National Education Policy 2019 has been made public. It will be interesting to note some of its provisions which underline the need for peace and harmony in the country and to use education for achieving this vital goal. The word ‘peace’ is used in the NEP seven times and the word ‘harmony’ once.[16] Some of its relevant paras go like this:

- “In the indirect method, the contents of languages, literature, history, and the social sciences will incorporate discussions particularly aimed at addressing ethical and moral principles and values such as patriotism, sacrifice, nonviolence, truth, honesty, peace, forgiveness, tolerance, mercy, sympathy, equality and fraternity.” (P.4.6.8.1)

- “Some of these Constitutional values are: democratic outlook and commitment to liberty and freedom; equality, justice, and fairness; embracing diversity, plurality, and inclusion; humaneness and fraternal spirit; social responsibility and the spirit of service; ethics of integrity and honesty; scientific temper and commitment to rational and public dialogue; peace; social action through Constitutional means; unity and integrity of the nation, and a true rootedness and pride in India with a forward-looking spirit to continuously improve as a nation.” (P.4.6.8.3)

- “All children will be a part of an inclusive and equitable society when they grow up, which in turn will raise the peace, harmony, and productivity of the nation.” (NEP 2019, 138)

Reading of these paras reassures that such values as peace, harmony, and equality have been duly highlighted by the policymakers. However, the outcome of these high ideals depends on their realization in society at large.

Recommendation

The following recommendations may be found useful:

- There is a need to undertake research and studies for proper understanding of impact of communal situation on the educational attainments of Muslims and other marginalized sections of the country for developing due policy and schemes.

- There is a need that peace education should be promoted in an effective way both in schools and colleges and also in society.

- Muslims should take the advantage of significant presence of non-Muslim students in their institutions for bridge building.

- Human rights networks should evolve in the educational institutions to resist violation of peace and harmony there.

- Muslim students should be oriented and trained in life skills for facing the challenge of hate and prejudice within and outside the campuses.

___________________________________________________________

[Author is President, Institute of Policy Studies and Advocacy, New Delhi,

and may be contacted on: agwandelhi@gmail.com]

___________________________________________________________

[1] http://bit.ly/2Fslq4p

[2] http://bit.ly/2ZFuSca

[3] http://bit.ly/2Fslr8t

[4] http://bit.ly/2ZNhwen

[5] http://bit.ly/2ZNhwen

[6] Ibid

[7] http://bit.ly/2FCneYT

[8] Sachar Committee Report, 2006, p 55,61 and 66

[9] Raheel Dhattiwala. Muslims of Ahmedabad: Social Changes Post-1993 andPost-2002 Riots. (2006). WISOMP: New Delhi, P.

[10] http://bit.ly/2ZF4krO

[11] http://bit.ly/2FqQP7d

[12] Graham K. Brown. The influence of education on violent conflict and peace: Inequality, opportunity and the management of diversity. UNESCO IBE. Prospects (2011) 41:191–204 https://purehost.bath.ac.uk/ws/files/257213/ Brown_Prospects.pdf

[13] Mohammed Abdi Adan1& John Aluko Orodho. http://bit.ly/2ZCMWUu

[14] http://bit.ly/2FslrFv

[15] Komol Singha. Conflict, State and Education in India: A Case Study of Manipur. American Journal of Educational Research. 2013; 1(6):181-193. doi: 10.12691/education-1-6-3

[16] Committee for Draft National Education Policy. Draft National Education Policy 2019. (2019). Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India: New Delhi. P477.

The post Quality education not possible without communal harmony appeared first on Muslim Mirror.

http://bit.ly/2ZxZQ6e

📢MBK Team | 📰MuslimMirror

Post A Comment: